Revisiting the L.A. Filming Locations of ‘Poetic Justice’ 30 Years Later

Poetic Justice, Singleton’s sophomore feature film, was released on July 23, 1993. It marked a tonal shift from his seismic feature debut Boyz N the Hood. In Poetic Justice, street violence, addiction, and racial injustice serve as the foundation upon which a love story is built.

10:11 AM PDT on July 18, 2023

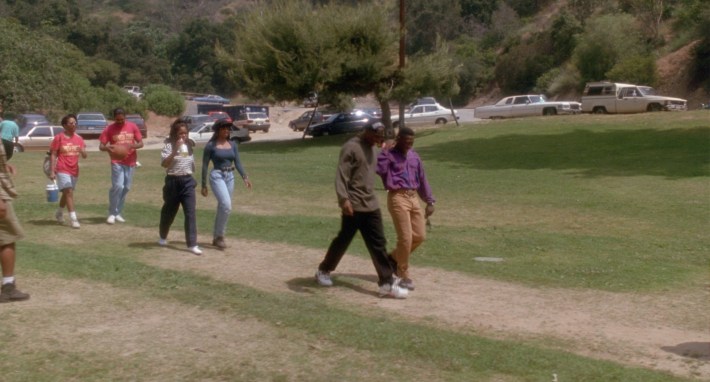

Lucky talks with some acquaintances. Screenshot via Columbia Pictures.

As groundskeepers weave between headstones on rideable lawnmowers, the smell of fresh-cut grass wafts through Inglewood Park Cemetery. Buzzing mower blades aside, it’s actually quite peaceful on this cool June morning, with the marine layer in full effect. After I’ve found the spot I’ve been looking for, a specific patch of grass between two weather headstones, a sudden sense of sadness comes over me for a person I didn’t even know, but through his movies, I feel like I did.

Writer-director-producer John Singleton died in 2019 at the age of 51 after suffering a stroke. He is laid to rest at Forest Lawn Memorial Park - Hollywood Hills.

But it’s in this cemetery where Singleton creatively points his camera and rolls film on his lead actress, Janet Jackson, mourning over the grave of her character’s murdered boyfriend in Poetic Justice. The shots are fleeting and almost dreamlike. Singleton could have shot the scene in almost any large cemetery in L.A., but he didn’t. This spot about 15 miles south of Forest Lawn, in Singleton’s beloved South Central Los Angeles, feels, at this moment, more significant than the star-studded Valley cemetery where Singleton is interred. After all, it’s in this part of town that the filmmaker left his cinematic soul.

Poetic Justice, Singleton’s sophomore feature film, was released on July 23, 1993. It marked a tonal shift from his seismic feature debut Boyz N the Hood. In Poetic Justice, street violence, addiction, and racial injustice serve as the foundation upon which a love story is built.

Justice (Janet Jackson) is a young beautician and budding poet. The loss of her mother to suicide as a little girl, the death of her grandmother to whom she was close, and the murder of her first love has contributed to the emotional walls that Justice has built around herself. She wears black from head to toe, buries herself in work, and is all but consumed by her grandmother’s aged and cavernous home.

When Justice’s car doesn’t start, she reluctantly hitches a ride to a hair show in Oakland in a mail truck alongside her best friend Iesha (Regina King), Iesha’s postal worker boyfriend Chicago (Joe Torry), and his co-worker Lucky (Tupac Shakur). Lucky, who also has artistic aspirations, has recently taken on the awesome responsibility of raising his six-year-old daughter away from the girl's drug-addicted mother. Out on the road, Justice’s walls slowly crumble.

Whereas Boyz was set and shot in one community, Poetic Justice was larger in scope. It had more than double the budget of Boyz. A little over one hour of screen time in Poetic Justice was filmed in the L.A. area, including a couple of “road” locations doubled in town and sets built at the Sony lot in Culver City. That leaves roughly 45 minutes of the film that was shot at coastal locations like Pismo Beach and Big Sur and in Oakland.

“Poetic Justice is a road picture,” says the film’s producer, Steve Nicolaides, “and those are my most fun movies, but they are also the fucking hardest movies to do.” Nicolaides, who also produced Boyz and Singleton’s reimagining/semi-sequel of Shaft (2000), says they needed a location manager with out-of-town experience.

Enter location manager Kokayi Ampah. Nicolaides hired him upon the recommendation of a colleague that worked with Ampah on White Men Can’t Jump (1992). One of the biggest credits to Ampah’s name pre-Poetic Justice was Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple (1985), which was shot in North Carolina.

On first meeting with Singleton, Ampah says, “He was a very energetic, driven young man.” He adds, “John was like my younger brother.”

Nicolaides and Ampah presume that Singleton’s critical and commercial success with Boyz likely opened some doors to locations on Poetic Justice.

Nicolaides recalls, “On Boyz N the Hood, if you said, ‘We’re doing a John Singleton movie,’ they’d say, ‘What?’ On Poetic Justice, if you said, ‘We’re doing a John Singleton movie,’ they’d go, ‘Really?’”

“The name helps within certain groups, especially in the community,” says Ampah. “I don’t know that it helped that much in Monterey,” he quips.

In Veronica Chambers’ making-of book, Poetic Justice: Film-Making South Central Style, Singleton discussed his desire to shoot the film as much as possible on location rather than in a studio backlot.

“It’s too artificial,” he said of shooting on soundstages, “I wanted to be on location with my people.”

On the DVD commentary track for Poetic Justice, Singleton backed up this notion: “I’m from the hood. Just like Martin Scorsese is always gonna go back to his Italian roots, I’m gonna always go back to the ghetto.”

Nicolaides says, “John exuded a relaxation when he was in the hood. Even on Poetic Justice, when we started going up north to get to Oakland, his sort of relaxation on the set and his spirit in the [coastal] communities got a little more cautious.”

Ampah and Nicolaides recently spoke with L.A. TACO to break down the L.A. locations from Poetic Justice to mark its 30th anniversary.

The Drive-In

Principal photography on Poetic Justice began on April 14, 1992. About two weeks later, on Wednesday, April 29, 1992, Singleton was on his way to Simi Valley to shoot at the Simi Drive-In, which was doubling as the Compton Drive-In in the opening scenes of Poetic Justice. In this sequence, Justice’s boyfriend, Markell (Q-Tip), is shot and killed in front of her.

The Compton Drive-In opened in 1949 on Rosecrans Avenue, and it was still in operation when Poetic Justice was filmed, not closing until 1995. But by the early ‘90s, only a handful were operating drive-ins in the area. Nicolaides and Ampah both recall that the Simi Drive-In was selected because of operations and cost, as production would have required a drive-in to close for at least a few nights.

“The Simi Drive-In was closed down and quiet. Nobody cared,” says Nicolaides. “They welcomed the business. They welcomed the money… until the verdict came down.”

Upon hearing the report of the verdict that acquitted four LAPD officers involved in the beating of Rodney King, Singleton spontaneously headed to the Simi Valley Courthouse, where the trial had been held. There, he spoke on camera to reporters about the deep-rooted racial disparities of the American judicial system.

Filming in Simi Valley, the mostly White, middle-class Ventura County suburb about 40 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, took place from that fateful Wednesday night through Friday night. The production felt the shockwaves immediately.

Not counting main cast and crew, Ampah and Nicolaides estimate there were roughly a couple hundred African American extras on set.

Nicolaides says, “Every night before the shoot, if the call time was five o’clock in the afternoon, the sheriffs would show up at about four-thirty and find a reason to pop the trunks on their patrol cars and make sure everybody in positions of authority could see just how many big guns were stashed in the back of the squad cars.”

The production later shot un-permitted, second unit footage of the mail truck driving around burnt-out buildings in South L.A. Nicolaides says it’s fair to assume that Poetic Justice was the first feature film to capture the physical devastation of the riots on celluloid.

“Not a lot of it was used in the movie, but it was very, very important to everybody working on the show,” says Nicolaides.

One astonishing shot that made it into the final cut is a camera POV positioned inside the remnants of charred retail property on the southeast corner of 58th Street and Vermont Avenue as the mail truck drives by.

The Simi Drive-In was later demolished and redeveloped as a housing tract in the early 2000s.

209 Tierra Rejada Rd, Simi Valley (approximate address)

Leimert Park

Singleton kept an office in Leimert Park Village, one of L.A.’s historic hubs of African American art and culture.

“That was and is the Mecca of the Black community,” says Ampah. “That is the core of African American life in Los Angeles.”

“It’s kind of the West Village of South Central,” says Nicolaides. “John could get out of the car and walk down the street and everybody would say, ‘Hey, John. How’s it going?’ It would be like Bob Dylan walking down Bleecker Street in 1963.”

Singleton also lived in the same four bedroom-four bathroom house on Don Carlos Drive in nearby Baldwin Hills from 1990 until he passed.

Following Poetic Justice, Ampah, who is the industry’s first African American location manager, had been approached about doing locations for Singleton’s Higher Learning (1995) and Baby Boy (2001), but he was working on other projects.

“John and I would run into each other in different places,” says Ampah. “He would tell me about stuff he wanted to do. It was like a childhood excitement when he would tell me about these things.”

The two once crossed paths in Leimert Park, where Ampah was working on a location for Straight Outta Compton (2015), a film for which he came out of retirement.

“John was telling me, ‘Man, I got this project and, man, you wanna do this?’”

Ampah stayed un-retired a little while longer to do the locations for the original, Singleton-directed pilot (2016) of Snowfall, the L.A.-set FX series co-created by Singleton that ran for six seasons.

Leimert Park at the border of Crenshaw is featured in Boyz N the Hood, and the neighborhood is a central character in Baby Boy. But it’s Singleton’s affinity for Leimert’s artistic heritage and the area’s concentration of salons and beauty supply stores that makes the neighborhood a perfect setting for a story centered around a young, African American beautician and poet.

Shots in Leimert Park Village include Justice walking past a group of young Black men being detained by cops in front of the Vision Theatre. Singleton also filmed Justice honing her beautician skills inside the Universal College of Beauty, which has been located in an old pharmacy building on 43rd Place for 43 years. The beauty school’s L.A. roots go back 93 years to when it was founded as Henrietta’s School of Beauty Culture. The school’s website states that it “was the first school west of the Rocky Mountains to develop a course of study specifically designed to meet the hair care needs of African Americans.” It is still owned and operated by members the original family.

Also of note, Ampah says that retailers from Leimert Park Village brought out their goods for the film’s African Marketplace and Cultural Faire scenes. Set in Seaside, CA in Monterey County, the fair was actually shot at Disney’s Golden Oak Ranch in Newhall.

3419 W 43rd Pl, Leimert Park. Closest Metro lines and stop: Metro K Line - "Leimert Park Station" or Bus Lines 40, 105 or 210 - “Crenshaw/Vernon.”

Jessie’s Salon

The central location of Poetic Justice is Jessie’s Salon. Owned by the shop’s forthright, no bullshit businesswoman, Jessie (Tyra Ferrell) is described in Singleton’s published screenplay as the queen of the hootchies in tha hood. Her attire puts the E in ethnic, as she is wearing the hottest, most expensive outfit that can be bought at the Fox Hills Mall. Every chair in Jessie’s Salon is full. If you live in this community, this is the place your hair needs to be.

So much action takes place in the beauty salon that you have to wonder if the production found an empty storefront and built the salon rather than closing down an operating salon.

“We weren’t going to build,” says Ampah. “There’s too many beauty shops in the Black community to not get a real beauty shop.”

A visual motif that runs through some of Singleton’s work is the use of window frames within the actual film frame - in essence, a composition within an overall composition. Take Fudge’s (Ice Cube) dorm room patio looking into the living space in Higher Learning, or Jody’s (Tyrese Gibson) living room looking out to the front driveway in Baby Boy, or Jeremiah’s (André Benjamin) kitchen looking out to the backyard in Four Brothers (2005). The same was considered when looking for the salon location.

“It was, what was the look from the shop out? What did you see? How much character did you get from the neighborhood when you were walking into the shop? The layout of the shop, where the counters were, where the operators are,” says Ampah.

Through the process of elimination, the filmmakers centered on Hollywood Curl, a beauty salon on 54th Street in Windsor Hills. Ampah recalls that a family of African immigrants owned the salon.

Through the salon’s window, you can see the Southern California area office of the National Council of Negro Women, which is still located on 54th Street. The salon location, however, is no longer standing. In its place is a series of modular classrooms for the Mt. Sinai Early Learning Center.

3717 W 54th St, Windsor Hills. Closest Metro lines and stop: Bus Line 108 - “Slauson/Rimpau”, Bus Lines 40 and 210 - "Crenshaw/54th" or Metro K Line - "Hyde Park Station."

Angel’s Apartment

Immediately north of the 10 freeway off of Fairfax Avenue are two two-story apartment buildings that run almost perpendicular to one another. From the opposite side of the street, which is lined with small, bungalow-style houses, you can pick up the same wide angle that Singleton shot of Lucky and J-Bone (Tone Loc) walking from one building to the next. Power lines in the background appear as though they connect the two buildings. This is where Lucky’s daughter lives with her mother, Angel (Crystal Rodgers).

“It’s a very typical two-story, probably twenty-unit Southern California apartment building,” says Nicolaides. “You can find a million of them in Reseda. You could have found a million of them in North Hollywood before gentrification.”

But the location is a testament to the parts of town in which Singleton felt most inspired.

Ampah says, “John wanted to keep it real that way, and [made sure] that the community benefitted from the company shooting there.”

Nicolaides remembers arguing against the location because of the traffic noise from nearby Venice Boulevard and Washington Boulevard. The power lines also emitted the sound of static electricity. But overall it was visually interesting, he says.

Ampah says, “It’s kind of open air. You can get back and see the stairwells and all that stuff. It has an earthy, urban look to it.”

The scene is the only part of Singleton’s DVD commentary track where he conveys his creative thought process on a location:

“Look at this, this is some real ghetto shit.” He then goes on to explain how the shots are inspired by watching the films of Kurosawa. “Showing characters within their environment. Going from close shots to wide shots just to get a sense of the atmosphere of…the environment the characters live and thrive in.”

2211 S Genesee Ave, Mid-City. Closest Metro lines and stop: Bus Lines 33 or 217 - “Fairfax/Venice.”

Justice’s House

“We knew where these characters lived. We knew that [Justice] was in a moderately larger house that she’d inherited from her grandmother,” says Ampah. It wasn’t necessarily a difficult search, he says, but they needed a specific look. ”It was a grandmotherly kind of house that was somewhat a generation, or two generations, ahead of her character. She was living in the shadow of her relatives.”

The filmmakers decided upon a large craftsman home built in 1911 in the historic West Adams district.

“The craftsman architecture is from another century. And the character in that scene, where she ends up crying to [Steve Wonder’s “Never Dreamed You’d Leave in Summer”], it’s kind of about letting go of an older past that’s dragging you down,” says Nicolaides. “I think, in that way, that location really helped tell the story.”

2516 4th Ave, West Adams. Closest Metro line and stop: Bus Line 37 - “Adams/4th.”

The Johnson Family Reunion

Singleton says on the film’s commentary track that Poetic Justice was the only production shooting in L.A. that did not shut down due to the riots.

“It didn’t affect our schedule at all,” Ampah remembers. “We were in our community, so we felt safe - other than Simi Valley.”

Nicolaides, however, remembers that after production wrapped in Simi Valley, the production moved to Griffith Park at the start of the next week.

“There was no proximity to rioting or burnt-out buildings or any of that kind of stuff, and so we just kept on going,” says Nicolaides. His recollection of the schedule is confirmed in the Chambers book.

Along with the drive-in, one of the largest setups in Poetic Justice was that of the Johnson family reunion. After leaving a rest area in Paso Robles, Justice, Lucky, Iesha and Chicago spot the grand family picnic from the road, and the group decides to crash the party to get some barbecue.

“As long as the location didn’t bump you out of the storytelling, it was a no-brainer to stick to L.A.,” says Nicolaides.

“We weren’t going to stage a big scene like that on the road when we should do it in town,” says Ampah. “Are you going to take that many extras on the road?”

Ampah compares it to scouting a fort location in Key West, FL for Spielberg’s Amistad (1997). Aside from the architecture being incorrect, Ampah adds, “We needed 250 Black extras. There’s no two hundred Black people in Key West. So, if we were up in Monterey [on Poetic Justice], we’re not going to find that number of African Americans that live nearby. So, what we shot in Griffith Park were people from L.A.”

Ampah also says that it’s about access to the craftspeople and materials needed to create the environment of the family reunion. “It’s right here in L.A. So, economically it doesn’t make sense to take that scene on the road.”

Mineral Wells Picnic Area, Griffith Park. Closest Metro line and stop: Bus Line 96 - “LA Zoo.”

“Welcome to Oakland”

The mail truck rolls into Oakland at twilight. As it travels down a hillside road, a posted sign reads Welcome to Oakland. If it weren’t for the L.A. city skyline slightly visible in the upper right corner of the frame, sure, this could be Oakland.

The shot was done on Valley Ridge Avenue, about a three-minute drive from Singleton’s house.

Nicolaides says he may have done the second unit shot himself, but he doesn’t recall the specifics. Likewise, Ampah had already moved on to locations in Northern California and doesn't remember details of the setup.

Also doubled in L.A. was the Oakland hair show, which was shot inside a newly constructed, not yet operational wing of the L.A. Convention Center.

4575 Valley Ridge Ave, View Park. Closest Metro line and stop: Bus Line 102 - “Stocker/Valley Ridge.”

Please keep in mind that some of these locations are on private property. Do not trespass or disturb the owners.

Follow Jared on Twitter at @JaredCowan1.

Jared Cowan writes and podcasts about L.A. filming locations. He also works as a photographer and camera operator.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from L.A. TACO

The Ten Best Panaderías in Los Angeles to Get Your Pan De Muerto For Dia De Los Muertos

Los Angeles has the best pan de muerto scene in the country, from a sourdough variation to others that have been passed down through generations. Here are ten panaderías around L.A. where you can find the fluffy, gently spiced, sugar-dusted seasonal pan dulce that is as delicious as it is important to the Dia de Muertos Mexican tradition.

A New Genetically Modified ‘Low THC’ Hemp Was Just Approved by the USDA

The modified hemp plants are not available for purchase yet but when they are, they will likely appeal to hemp farmers since hemp that exceeds the .3% limit on THC can not legally be sold and must be destroyed.

Walnut Woman Gets Prison Time For Selling L.A. Homes That Weren’t Actually For Sale

Using other people's broker's licenses, Gonzalez listed the properties on real estate websites, even though many were not on the market, and she did not have authority to list them.

Family Awarded $13.5M In 2019 LAPD-Related Death Of Father

According to the suit, Jacob Cedillo was sitting on the sidewalk outside a Van Nuys gas station on April 8, 2019, at about 4:15 a.m. when police were called. Officers responded, immediately putting Cedillo in handcuffs even though he had not broken the law, according to the complaint.

L.A.’s 13 Most Infamous Murder Sites

While these sites' physical appearance or purpose may have changed over time, the legacy and horrors of what might have happened there linger forever. Once you know the backstory, walking or driving past them on a cool, crisp October evening is sufficient to provide you with a heaping helping of heebie-jeebies.