Grounded During White Flight: How Being a ‘White Boy’ from Maywood as It Transitioned to a 96 Percent Latinx Neighborhood Helped Me Become a Better Citizen and Parent

11:53 AM PDT on September 19, 2019

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hen I tell people I grew up in Maywood, I get one of two reactions. Those not familiar with the tiny suburb roughly six miles from downtown Los Angeles ask, “Where?” And those who are familiar with the working-class neighborhood go, “How are you from Maywood?”

There’s justification for the perplexment: I’m a white guy.

Maywood’s current population is roughly 96 percent Latinx. It’s also a sanctuary city and that population swells substantially when undocumented immigrants are taken into account. In other words, I don’t belong there. I’d be just as much of a gabacho standing at Maywood’s main intersection of Slauson Avenue and Atlantic Boulevard as I’d be hanging out in front of Tijuana’s Mercado Hidalgo.

As such, I’ve grown accustomed to the “how” question. It’s something I love answering, and not just because it allows me to provide context. It also gives me the chance to express gratefulness.

I’m not talking “gratefulness” in terms of being a white dude learning to see beyond a person’s skin color. That lesson should be rote to anyone with a shred of human decency, even as we live among people that proudly flaunt a shredless existence. I grew up in Maywood in the 1980s, during its transition from white suburbia to the Latinx hub that it is now. Living through the change cultivated a perspective within me that thrives on a deep appreciation of non-white cultures and contexts, to the point where I get twitchy if I’m exposed to a cadre of bougie Caucasians for too long. Maywood is why stepping into a carniceria with a Liga MX match blaring on the T.V. brings me a sense of warm comfort. I may not look like I belong in those situations, but frankly, I don’t care.

Maywood, From Beard-Growing Contests to Florerias and Taquerias

It’s ironic that Maywood arguably boasts L.A. County’s whitest sounding origin story. The city unofficially came to be in 1919 as a rancho-turned-housing tract that derived its moniker from a popular real estate agent named May Wood. It officially incorporated five years later and celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1949 with a beard-growing contest among other folksy, mayonnaise-splattered events. It thrived in the postwar era as a bedroom community seemingly custom-built for the working-class souls who toiled in the steel mills, aluminum plants, and glass factories in nearby Vernon and Commerce, as did other Maywood-adjacent cities like Bell, Huntington Park, Cudahy, and Bell Gardens. Then the late ‘70s happened, plants started to shutter, and white families relocated to new job markets, leaving behind homes of sharply declined property values for first-and second-generation Mexican-and-Central American immigrant families to snap up.

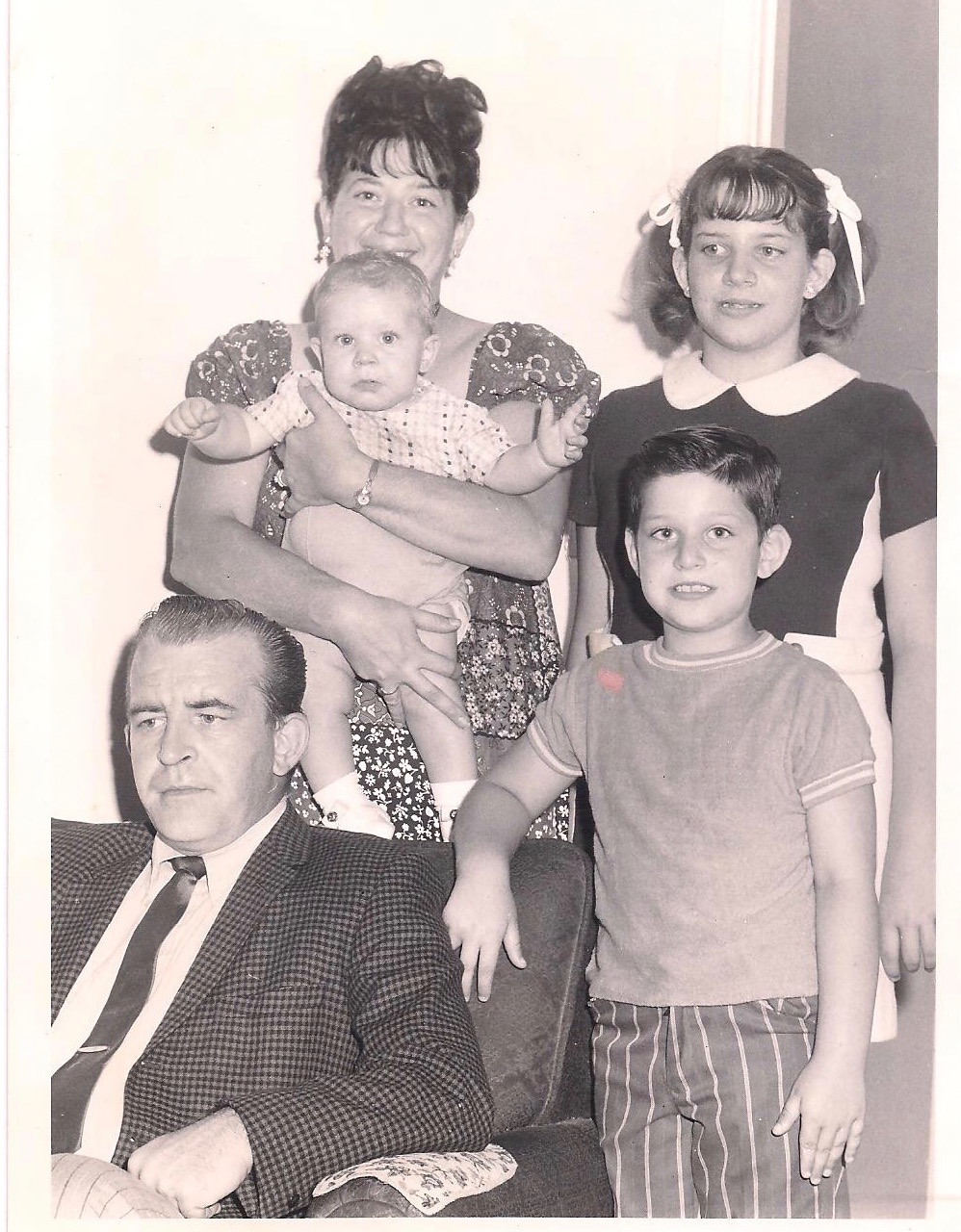

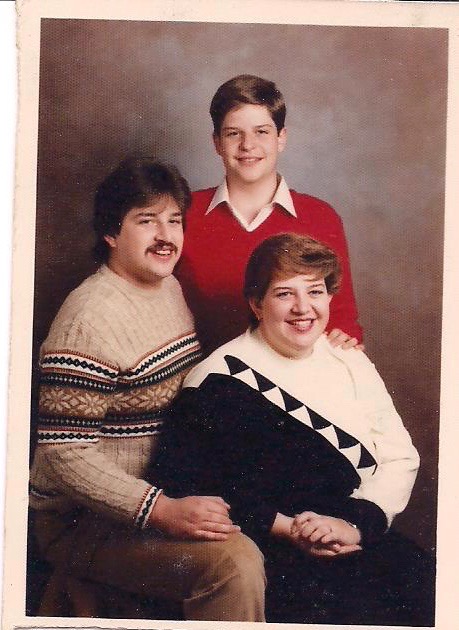

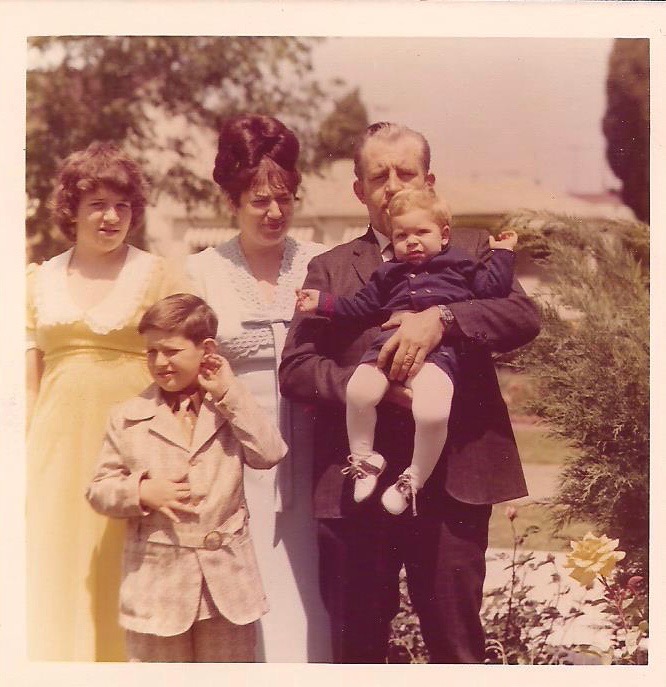

Our family stayed in our Maywood bungalow on Mayflower Avenue even after Bethlehem Steel, the mill my father worked at, closed in 1981. My grandparents owned our home and they lived two houses down in the same bungalow court, which made sticking around an easy call. This gave me courtside seats to the city’s transformation, which was in medias res by the time I was capable of making memories. Everything was fantastically diverse during my elementary school days, a multicultural utopia that in retrospect felt like a global community in its purest form. Our home was flanked by Mexican families, but it was also across the street from the Greek family that owned Apollo’s, the killer greasy spoon located four blocks north. Two of our closest family friends were immigrants—one Cuban, one German. My siblings both dated Mexicans in high school, and I had a 2nd-grade crush on a white girl named Heather (who moved away mid-year, natch). The church we attended, Zion Lutheran, staffed a Latino ministries pastor, even though the congregation was as white as the Christ Crispies served at communion.

Then the late ‘70s happened, plants started to shutter, and white families relocated to new job markets, leaving behind homes of sharply declined property values for first-and second-generation Mexican-and-Central American immigrant families to snap up.

The city’s infrastructure was a different story. Even as its demographics evolved, Maywood clung tightly to the look of post-war white bread idealism. The corner Thrifty drug store housed a diner with periwinkle blue banquettes. The office stationery and supply shop looked like a Doris Day set piece through its yellow-tinted windows. We bought bouquets from Ron’s Flower Shop, so named after the white, square-jawed owner. We colloquially called the local auto shop “Floyd’s,” after the middle-aged grease-smeared white guy that seemed to constantly tinker with our van’s motor mount. The neighborhood record store, Psychedelic Sounds, poked past the Eisenhower era with its name, but it pumped the latest sounds in rock, punk, and metal and pushed rap and Morrissey to its dark corners. It wasn’t quite Main Street U.S.A., but it came close to matching its ethos if you didn’t actually look at the residents.

This changed around 1986, right about the time Maywood’s first-ever McDonald’s plopped its golden arches on Slauson and Atlantic. Thrifty packed up its chocolate malted krunch ice cream and left. Ron and Floyd split town. Psychedelic Sounds faded like a Zeppelin outro. The stationary store turned into a typewriter mausoleum before it went under. In their places were an increasing number of businesses more representative of Maywood’s burgeoning legal and increasingly undocumented Latino demographic. We were sad to see our old favorites go, but we never flinched at the shift. This was still our community, and we felt compelled to act as such. We explored. We built up new relationships. We treated it like the home it still was because that’s what we felt we should do.

The Thrifty's was replaced by a relatively new concept called the 99 Cent Store. Both spots removed the veneer of middle-class white suburbia in a way that a new florista or taqueria did not.

Understanding the shift’s implications, however, was a different animal, particularly from my idealistic 14-year-old perspective. While the McDonald’s opened with much fanfare, Nix Check Cashing opened in the same shopping complex a couple of months later with significant muteness. The Thrifty's was replaced by a relatively new concept called the 99 Cent Store. Both spots removed the veneer of middle-class white suburbia in a way that a new florista or taqueria did not. They were businesses poised to pounce on citizens of a town suffering from an increasingly severe economic free-fall, one that would make Maywood and its surrounding cities one of California’s poorest regions by decade’s end. I didn’t realize this at the time, and this ignorance caused me pain.

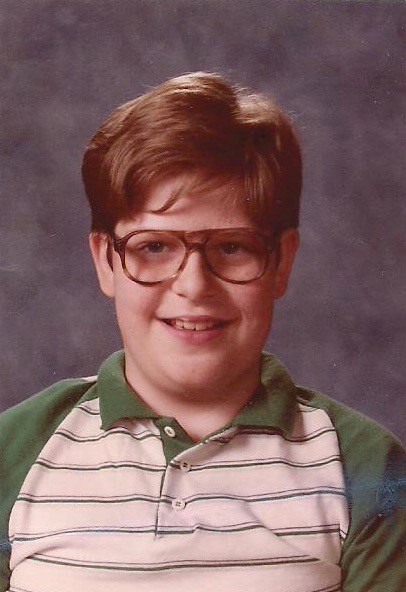

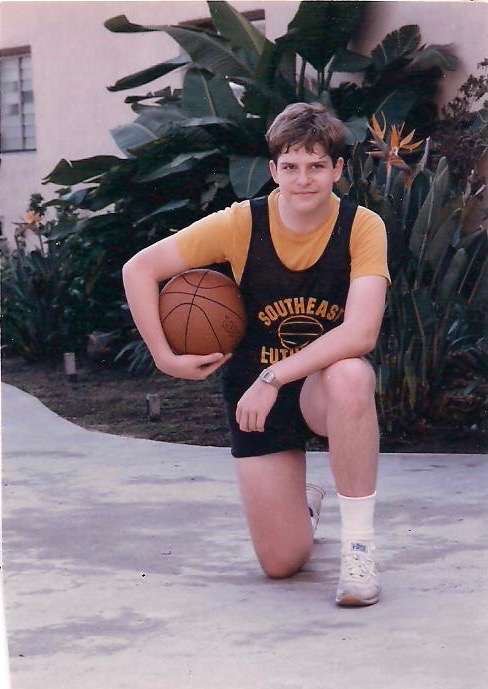

“White Boy” and the School of Maywood Hard Knocks

Full disclosure: I was a supreme dork as a kid. I was a doughy asthmatic in horn-rimmed glasses and “husky” clothes that took corrective physical education for three years to improve my potato-like dexterity. I was an easy target for elementary school playground teasing, and kids allegedly cooler than me routinely let me know my place on the asphalt hierarchy by reminding me of my weight and eyesight issues. The taunts began taking a dark turn around 1985, when I started attending a tiny, absurdly cost-effective parochial Lutheran junior high and high school combo in nearby South Gate. There were roughly 150 kids there at any given time, spread across six grades. All but 15 to 20 were Latino or African-American, with the former ethnicity being the dominant presence. Shortly after I started 7th grade, the school’s Latino bullies and agitators also started to callously throw around “white boy” as an epithet. It was never gringo or gabacho then—always “white boy.” Sometimes they’d knock books from my hands or stomp on my feet, which was preferable to the other occasions where they’d shove me, smack me, or spit in my face. It made me hate going to school despite having friends there.

At the time, being bullied as a “white boy” didn’t make much sense to me.

And you know what? I forgive them because I doubt they were angry at me. I was just symbolic of what truly drove their ire. I didn’t always think this clearly. At the time, being bullied as a “white boy” didn’t make much sense to me. I knew it wasn’t because of money. It was obvious I wasn’t rich. Pro Wings are not the footwear of the bourgeoisie, especially when they’re a brand upgrade from the previous pair of sneakers. I also knew it wasn’t because I was a dork. I continued to be picked on for my nerdy tendencies.

Now that I’m older and perspective has settled in, the only reason that makes sense to me is because of my whiteness—or rather, what my whiteness represented to my Latino tormentors. It meant a free pass to gaining trust, respect, and opportunity, something that they had to work just short of bleeding to achieve if it was achievable for them at all. Having these elements in my back pocket would presumably make it easier for me to leave Maywood, like so many other whites before me; when I did, I was leaving behind—and leaving them—an inescapable socio-economic quagmire destined for several decades of bleakness. They had every right to be pissed, and I can’t be angry at that, although I could have done without the loogies.

This talk doesn’t come from MAGA hat-wearing individuals discussing “brown people” as much as they come from average-looking folk casually and pithily referencing things like “Mexican neighborhoods.”

I didn’t come to this realization until I graduated high school in 1990. We had moved out of Maywood and into Orange County a few months prior—the commute to finish school sucked—and my universe gradually accumulated an abundance of white people. What I’ve encountered in some circles of whiteness over the years amounts to privilege by subtraction; thoughts and philosophies containing somewhat nuanced disdain and derision for cities like Maywood or areas sharing Maywood’s ethnic makeup.

This talk doesn’t come from MAGA hat-wearing individuals discussing “brown people” as much as they come from average-looking folk casually and pithily referencing things like “Mexican neighborhoods.” This scoffing hints of the implied mistrust and xenophobia that tends to inadvertently damage and oppress. Their actions always imbue a sense of empathy toward L.A.’s Latinx, including the ones that roughed me up. This is probably I tend to verbally mark these unwitting judgemental types as stupid white people.

Maywood May Not Be Perfect, But It’s Still My Home

If you get a steady amount of green lights on Slauson Avenue these days, you can cut through Maywood’s width in under five minutes. I took this route in early September, starting yards away from where Bethlehem Steel once stood. Bright, colorful buildings with establishments ending in “ria” festoon the west side, creating an aesthetic in tune with a bustling Tijuana commercial district. Crossing Atlantic Boulevard disrupts this vibe. Amid the smattering of older storefronts shilling DIY wares and blue-collar services are newer structures that seem to recall days before the city’s financial struggle. Chief among these is the Maywood Center for Enriched Studies, a massive magnet school juxtaposing a 2017 establishment date with a groovy early 1970s design. It wasn’t planted without controversy. Google Maps still grants visual access to the protest poster-laden neighborhood that the school displaced, but it nonetheless seems to suggest a community looking to pull itself from a tailspin.

[My daughters] have participated in quinceaneras, bury their fruit in blankets of tajin, and roll their eyes at the xenophobia of stupid white people just as hard as I do, if not harder. It’s glorious to behold.

Nobody knows this, or at least cares to, not that anyone could be blamed. Maywood is so synonymous with political corruption, it’s almost easy to gloss over the gritty, crime-riddled reputation it’s cultivated over the last thirty years. It’s been this way for more than a decade - things haven’t improved much since the city gutted its police force and city services in 2010. I’ve grown accustomed to heartbreak whenever the city gets mentioned on TV or print, because I know it’s going to be about something bad. It hurts every time.

Maywood still means so much to me because of how substantially it impacted my worldview. It’s an outlook my wife and I try to impart on our teenage daughters, and we, fortunately, have a unique opportunity to do so. Our current home is about a football field away from Santa Ana, a city whose 78 percent Latinx population is as close to Maywood’s population makeup as you can find in Orange County. Multiculturalism is our daughters’ way of life, and it’s fully embraced, particularly since they attend a Latinx-dominant high school. They’ve participated in quinceaneras, bury their fruit in blankets of tajin, and roll their eyes at the xenophobia of stupid white people just as hard as I do, if not harder. It’s glorious to behold.

There are still plenty of opportunities to share this glory with others. A few weeks ago, our youngest daughter relayed a conversation she had with one of her friend’s fathers. The conversation essentially boiled down to the dad repeatedly confirming that we were okay with our daughter hanging out with a Latino family on account of us being white. I can’t wait to meet this gentleman and tell him I’m from Maywood. I’m hoping he’s heard of it; if he has, I’m sure he’ll understand where I’m from.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from L.A. TACO

The Ten Best Panaderías in Los Angeles to Get Your Pan De Muerto For Dia De Los Muertos

Los Angeles has the best pan de muerto scene in the country, from a sourdough variation to others that have been passed down through generations. Here are ten panaderías around L.A. where you can find the fluffy, gently spiced, sugar-dusted seasonal pan dulce that is as delicious as it is important to the Dia de Muertos Mexican tradition.

A New Genetically Modified ‘Low THC’ Hemp Was Just Approved by the USDA

The modified hemp plants are not available for purchase yet but when they are, they will likely appeal to hemp farmers since hemp that exceeds the .3% limit on THC can not legally be sold and must be destroyed.

Walnut Woman Gets Prison Time For Selling L.A. Homes That Weren’t Actually For Sale

Using other people's broker's licenses, Gonzalez listed the properties on real estate websites, even though many were not on the market, and she did not have authority to list them.

Family Awarded $13.5M In 2019 LAPD-Related Death Of Father

According to the suit, Jacob Cedillo was sitting on the sidewalk outside a Van Nuys gas station on April 8, 2019, at about 4:15 a.m. when police were called. Officers responded, immediately putting Cedillo in handcuffs even though he had not broken the law, according to the complaint.

L.A.’s 13 Most Infamous Murder Sites

While these sites' physical appearance or purpose may have changed over time, the legacy and horrors of what might have happened there linger forever. Once you know the backstory, walking or driving past them on a cool, crisp October evening is sufficient to provide you with a heaping helping of heebie-jeebies.